Environmental Impacts of Aggregate and Stone Mining in New Mexico

Center for Science in Public Participation

Rural Conservation Alliance

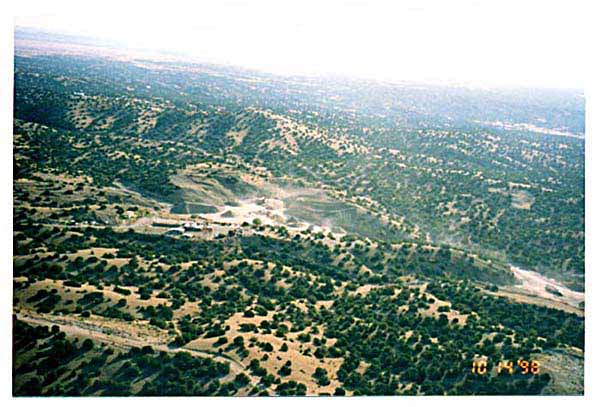

dusty gravel mine 1998, Cerrillos

Environmental Impacts of Aggregate and Stone Mining in New MexicoPrepared by Steve Blodgett, M.S.

Center for Science in Public ParticipationFor

Rural Conservation AllianceJanuary 2004

dusty gravel mine 1998, Cerrillos

~ Executive Summary Aggregate, stone, and industrial mineral mines are common across New Mexico, with more than 200 such operations having active permits in 2001. Although aggregate and stone mines are not regulated under the New Mexico Mining Act, they are registered with MMD and permitted by NMED for air and water quality purposes. In addition, portable crusher/screen plants are allowed to operate for up to one year with minimal permitting requirements and then can move operations to other sites with no requirements for public notification. The primary environmental impacts from aggregate, stone, and industrial mineral mines in New Mexico are degraded air quality from stack emissions and disturbed areas on the mine and groundwater usage. Surface and groundwater quality impacts from such mines are relatively benign in New Mexico due to the semi-arid climate and lack of perennial streams. Other environmental impacts include increased traffic on new or improved or existing roads; cumulative impacts as construction materials are hauled, stockpiled, and spread on highway and building construction projects; and aesthetic degradation caused by both active and abandoned aggregate, stone, and industrial mineral mines in major viewsheds.

Existing environmental laws are limited in scope in regulating aggregate and stone mines in New Mexico. All but the largest of these mines are considered minor sources of air pollutants and are allowed to emit limited quantities of Total Suspended Particulates, sulfur compounds, nitrogen dioxide, and Volatile Organic Compounds under their air quality permits. These emissions may have detrimental effects on certain rural communities (e.g., Velarde, Los Cerrillos, Socorro), but the state does not consider these impacts to be significant or to pose serious public health hazards. Existing regulations do not account for the concentration of such mines in and around urban areas where the majority of highway and building construction occurs. Because aggregate and stone mines are exempted from reclamation and regulatory requirements under the New Mexico Mining Act, these mines are not required to re-vegetate or reclaim their operations. Consequently, hundreds of abandoned and inactive mines are located in every county of the state.

The following recommendations are made to better manage environmental problems and mitigate the effects of aggregate, stone, and industrial mineral mines.

1. Deny operating permits to new operations if inactive or abandoned mines located in appropriate areas could be re-opened to provide the same resource. New operations should be permitted only if no other suitable materials are available in a given area. This would make better use of existing resources in areas where disturbance has already occurred and prevent the random and incoherent development of aggregate and stone mines.

2. Enforce existing mine and mill air quality permits strongly and consistently. The state seldom enforces the terms of air quality permits and rarely issues Notices of Violation or fines allowed under the Air Quality Act. This would require that the state hire more inspectors and make certain "problem" mines and mills come into compliance to set an example for all operations.

3. Deny permits to mines that propose locating in areas unsuited for mining. Mines should not be allowed to operate near Native American "sacred sites," residential neighborhoods, historic rural communities, or in areas where the resulting "scar" will ruin a scenic viewshed.

4. Encourage the use of re-cycled materials in building and road construction. "Glassphalt," "Plasphalt," and used tires could replace or supplement aggregate, crushed rock, base course, sand, and gravel in highway construction. Likewise, use of re-cycled materials could be encouraged in the construction industry. This would reduce the need to open new mines and help with the problem of overloaded landfills. Because re-cycled materials are not currently competitive with many highway construction materials, the state and federal government will likely have to subsidize the use of re-cycled materials. However, over time it is likely that re-cycled materials will become more widely used and the cost differential between road construction and building materials and re-cycled materials will narrow.

1. IntroductionThis report has been prepared for the Rural Conservation Alliance (RCA) to identify the environmental impacts of aggregate and stone mining in New Mexico and to recommend mitigation measures to address these impacts. Aggregate and stone mining is not regulated under the New Mexico Mining Act, but the New Mexico Environment Department (NMED) issues air quality and water quality permits for these mines and their associated crushing plants. "Aggregate and stone mining" is the term used by the Mining and Minerals Division (MMD) and includes the following types of materials as listed in "Mines, Mills, and Quarries in New Mexico" (Mining and Minerals Division and others, 2001): shale and clay; sand and gravel; aggregate; base course; crushed rock; limestone; fill dirt; top soil; caliche; scoria; "red dog" (coal clinker); rip rap; agate; travertine; and dimension stone. Mines producing these materials are exempted from reclamation requirements under the New Mexico Mining Act; but each of these mines must be registered with MMD and must have the appropriate permits from other agencies like MSHA (Mine Safety and Health Administration) and DOT (Department of Transportation). In addition to state and federal regulations, some of the 33 counties in New Mexico have land use regulations that are administered through the county Planning Department.

Aggregate and stone mining produces materials that are used in road construction (aggregate, base course, crushed rock, sand and gravel); building construction and landscaping (topsoil, fill dirt, rip rap, scoria, travertine, dimension stone); and other general construction uses. Because the economics of construction materials depend heavily on the proximity of the mine to the point of use, aggregate and stone mines are found in the highest concentrations in urban areas where most home and office construction and general highway construction occurs. However, these mines are located in every county of the state and many of the largest of the mines producing road construction materials are situated immediately adjacent to highways in order to reduce haul costs. Because haul costs (i.e., fuel, labor, and maintenance) are the single largest variable in determining the cost of material in road construction, sand and gravel mines are often opened near to a specific road project and then abandoned once the project is completed. Consequently, the majority of both active and inactive sand and gravel mines are located along interstate highways or major state and county roads.

New Mexico had more than 200 permitted aggregate, stone, and industrial mineral mines in 2001 (Tables 1 and 2). Total employment for all industrial mineral and aggregate mines was 1710 in 2001; total combined revenues for industrial mineral and aggregate production was $2,025,426, with 48% of that total coming from aggregate and stone mines (MMD and others, 2001, Table 1). No data are available for the areas disturbed by each of these mines but most operations range in size from one to 20 acres. In the Rio Grande Valley, most aggregate and stone operations are mining deposits in the Santa Fe Group, a thick sequence of Tertiary to Holocene-age sediments deposited in the Rio Grande Rift, a major structural feature that runs from Leadville, Colorado to the Las Cruces-El Paso area (Hawley and others, 1978). However, sand and gravel deposits are located in every county of the state and are mined based on their proximity to the point of final use, quality of the materials in the deposit, and accessibility. No estimates have been made for the volume of aggregate and stone deposits in New Mexico, but it is generally assumed that resource development is limited only by proximity to construction projects and transportation costs and not by the size or quality of deposits.

Table 1. Aggregate and Stone Mines in New Mexico, 2001 (MMD and others, 2001).

* s/c= shale and clay; sg= sand and gravel; l= limestone; bc= base course; g= gravel; s= sand; fd= fill dirt; t= topsoil; c= caliche; agg= aggregate; sco= scoria; aga= agate; rd= red dog (clinker); cr= crushed rock.

County Types of Mines* Number Bernalillo s/c; bc; l; fd; sg 5 Chavez sg; g; bc; t; fd; s; agg 8 Cibola l 1 Colfax bc; g; sg 4 Curry bc; c; cr 9 De Baca sg; cr 4 Doña Ana sg; fd; rd; sco; bc; agg; cr; c 26 Eddy fd; bc; cr; s 1 Grant l; bc; s; sg; fd 5 Hidalgo sg 2 Lea cg; bc; fd; s; c; t 3 Lincoln cr; bc; fd; sg 2 Luna aga; agg; bc; g; cr 4 McKinley l; rd; s; bc; sg 7 Mora sg 1 Otero s; bc; g; t; c; sg; cr; fd; agg 7 Quay bc; sg; agg 2 Rio Arriba sg; sco 5 Roosevelt cr; c; bc; fd; sg 2 San Juan sg; agg; s; fd; cr; bc; g 16 San Miguel cr; g; fd; bc; sg 4 Sandoval Ssg; bc; s; cr; g 11 Santa Fe sco; bc; cr; fd; t; g; s 8 Sierra sg; bc; fd; g 3 Socorro agg; sg; bc; cr; fd 5 Taos sg; bc; cr; fd; g; s 10 Torrance bc; agg; g; fd; c; cr 5 Union sco 2 Valencia sg; cr; s; bc 4 Total 165 Table 1 above lists the permitted aggregate and stone mines in New Mexico by county for 2001, the most recent year for which statistics are available. This table does not include the numerous aggregate and stone mines located on Indian land (19 pueblos, Jicarilla and Mescalero Apache, and Navajo Nation lands, including Alamo, Ramah, and To'haji'lee), which are regulated under Tribal and federal laws.

In addition to permitted state mines and Indian mines, several hundred abandoned or inactive sand and gravel, aggregate, and other mines that produced construction materials are scattered across the state. Few of these mines have been formally reclaimed, although some have been naturally re-vegetated to some extent. Note that these mines do not include industrial minerals like gypsum, calcite, perlite, pumice, salt, silica, humate, zeolites, and mica. Table 2 lists mines that produced industrial minerals in New Mexico in 2001. These mines are listed here because some types of industrial minerals mining (e.g., gypsum, calcite, perlite, silica, zeolites, and mica) produce environmental impacts similar to aggregate and stone mines. Industrial minerals are covered under the New Mexico Mining Act so these mines have formal permitting and reclamation requirements.Table 2. Industrial Mineral Mines in New Mexico, 2001 (MMD and others, 2001).

*c= clay; g= gypsum; p= perlite; ca= calcite; s= salt; si= silica; h= humate; m= mica; z= zeolites; d= dimension stone; o= other.

County Types of Mines* Number Bernalillo c; g; p 3 Cibola P 3 Doña Ana c; g; ca 3 Eddy S 4 Grant Si 4 Hidalgo Si 1 McKinley H 3 Otero O 1 Rio Arriba p; m 2 Sandoval g; h; p 7 Santa Fe p; si 5 Sierra Z 1 Socorro P 1 Taos p; m 3 Valencia D 1 Total 42 2. New Mexico Air Quality Regulations

Regulations governing air quality in New Mexico are found in the NMAC Title 20, Chapter 2. The relevant regulations for aggregate and stone mines are found in Chapter 2, Part 3 (Ambient Air Quality Standards [AAQS]). The preamble to Part 3 (NMAC 20.2.3.108) makes the following statement: "Ambient Air Quality Standards are not intended to provide a sharp dividing line between air of satisfactory quality and air of unsatisfactory quality. They are, however, numbers which represent objectives that will preserve our air resources. It is understood that at certain times, due to unusual meteorological conditions, these standards may be exceeded for short periods of time without the addition of specific pollutants into the atmosphere (emphasis added)."

Those parameters regulated under AAQS include total suspended particulates (TSP); sulfur compounds (SO2, H2S, total reduced sulfur); carbon monoxide (CO); and nitrogen dioxide (NO2). Table 3 below lists the AAQS for each of these parameters.Table 3. New Mexico Ambient Air Quality Standards

(NMAC 20.2.3.109-20.2.3.111).

Parameter Standard Total Suspended Particulates mg/m3 24-hour average 150 7-day average 110 30-day average 90 Annual geometric mean 60 Sulfur Compounds ppm Sulfur dioxide Annual arithmetic average 0.02 24-hour average 0.10 Hydrogen Sulfide 0.010 Total Reduced Sulfur 0.003 Carbon Monoxide ppm 8-hour average 8.7 1-hour average 13.1 Nitrogen Dioxide ppm 24-hour average 0.10 Annual arithmetic average 0.05

The regulations define "major stationary sources of air pollutants" to include those sources that directly emit or have the potential to emit 100 or more tons per year of any air pollutant. Among the categories of stationary sources listed in NMAC 20.2.70 Q2 are portland cement plants (c); lime plants (k); and phosphate rock processing plants (l). The other 23 stationary sources listed are associated with coal, oil, metallic mining/milling, and power plants. Thus, with the exception noted above, aggregate, stone, sand, gravel, and industrial mineral mines and mills are not considered "major stationary sources" of air pollutants under the New Mexico regulations.The Air Quality Bureau (AQB) in NMED maintains 34 monitoring sites across the state for ambient air quality. Two additional sites are monitored for meteorological parameters only. The state runs 13 ozone monitors, nine NO2 monitors, eight SO2 monitors, 3 CO monitors, and 35 particulate monitors (both continuous and intermittent) that monitor both PM 10 and PM 2.5 particulates. Most of the NMED monitors are located in Doña Ana County along the border with El Paso and Juarez where the air quality is poor. San Juan County, location of the majority of oil, gas, and coal production in New Mexico, has the next highest number of monitoring stations. In other areas of the state, monitoring is performed according to need. For example, in Santa Fe County the only pollutants monitored are carbon monoxide and particulates because of the absence of industries that would produce other pollutants.

During 2001-2002, Bernalillo County (Albuquerque) received a grant from EPA for toxics monitoring. A total of 19 pollutants, including heavy metals, aldehydes, and various VOCs were monitored. The AQB does not have jurisdiction over facilities in Bernalillo County (Albuquerque) or on Indian lands, where regulation is done by either EPA or Tribal programs.

Only 3 areas in the state have experienced chronic exceedances of EPA standards. Two of those areas are in Doña Ana County (for ozone and PM-10 non-attainment) and one area is in Grant County around the Hurley smelter (SO2 non-attainment), which is now inactive. Many areas in Doña Ana County experience elevated particulate levels during high wind events. Although these are natural events, the Air Quality Bureau has implemented a Natural Events Action Plan (NEAP) in order to mitigate any man-made contributions such as uncontrolled construction sites.

Aggregate and stone mines are required to obtain air quality permits from NMED that specify the amount of particulate matter or other pollutants a given mine or mill is allowed to emit. The AQB conducts emission inventories by performing dispersion modeling. For a point source like an aggregate or stone mine, the AQB collects the following information for an emissions inventory (NMED AQB Dispersion Modeling Section Web page):

1. Facility name; physical location; contact information;

2. Actual emissions by pollutant, including criteria pollutants, precursor pollutants, hazardous air pollutants (HAPs), and New Mexico toxic air pollutants (TAPs);

3. Actual operation status, hours per year, and per cent throughput per quarter;

4. Emission stack parameters; and

5. Annual process or fuel combustion rates and fuel characteristics.The AQB Permitting Section processes permit applications for industries that emit pollutants to the air under two categories: New Source Review (NSR) or Title V. The NSR group is responsible for issuing Construction Permits, Technical and Administrative revisions or modifications to existing permits, Notices of Intent (NOIs) for smaller industrial operations, and No Permit Required (NPR) determinations. Construction permits (under NSR) are required for all sources with the potential emission rate greater than 10 pounds per hour or 25 tons per year of criteria pollutants (e.g., NOx and CO). Operating permits under Title V are required for major sources that have the potential to emit more than 100 tons per year for criteria pollutants or for landfills greater than 2.5 million cubic meters. Major sources also include facilities that have the potential to emit greater than 10 tons per year of a single Hazardous Air Pollutant or 25 tons per year of any combination of HAPs (NMED AQB Permitting Section Web page).

Table 4 lists the permitted air quality parameters for aggregate, stone, and industrial mineral operations that have applied for permits in 2003. These are examples of the various types of mines and processing facilities that are permitted by NMED and registered with MMD as aggregate or stone mines or industrial mineral mines or plants. Under the criteria listed above, most aggregate and stone mines and mills in New Mexico are permitted under the NSR program and are issued Construction Permits or revisions or modifications to existing permits. None of the operations listed in Table 4 would be listed as a major source for criteria pollutants and thus none are permitted under Title V.

Some large sand and gravel mines or cement plants in Bernalillo County would be permitted as major sources of criteria pollutants, but these operations are regulated by EPA Region 6 and not the AQB.

Table 4. 2003 Air Quality Permit Applicants for Aggregate or Stone Mines/Mills in New Mexico (2003 permit applications, NMED-Air Quality Web page). * TSP= total suspended particulates; PM 10= particulate matter < 10 microns diameter; NOx= nitrogen oxides; SO2= sulfur dioxide; CO= carbon monoxide; VOCs= volatile organic compounds; tpy= tons per year.

Owner County Type of Mine Permitted Emissions (tpy)* Robert E. Rivera Guadalupe Aggregate

Crusher plant

TSP= 13; PM 10= 7; NOx= 39; CO= 9; VOCs= 1 Hanson Aggregates WRP Torrance Aggregate

Crusher plant

TSP= 170; total emissions~ 362; NOx and CO< 100 Toro Mining & Minerals Luna Perlite

Mine/mill

TSP= 8; PM 10= 4 Coppola Concrete Santa Fe Concrete batch plant TSP= 18; PM 10= 25; NOx= 25; CO= 25 Twin Mountain Rock Colfax Aggregate

Crusher plant

TSP= 55; PM 10= 16; SO2= 10; NOx= 31; CO= 38; VOCs= 5 Robert Medina & Sons Concrete & Sand Taos Sand & gravel TSP= 46; PM 10= 23; NOx= 77; SO2= 14; CO= 17; VOCs= 4 Associated Asphalt, Inc.-Primary Plant Santa Fe Asphalt TSP= 11; PM 10= 6; NOx= 44; CO= 10; SO2/VOCs< 1 Associated Asphalt, Inc.-Pioneer Rip-Rap Plant Santa Fe Rip-rap TSP= 21; PM 10= 8; NOx= 19; CO= 5; SO2/VOCs< 1

3. Environmental Impacts

Documenting the environmental impacts produced by aggregate, stone, and selected industrial mineral mines in New Mexico is difficult because of several complicating factors:

--Lack of regulatory data collection for most mines due to exemptions under NM Mining Act (aggregate and stone mining);

--Complications in urban areas caused by numerous sources of air pollution;

--Lack of "baseline" data that would allow comparisons of pre-mining and active mining conditions for air and water quality;

--Naturally arid climatic and soil conditions that create conditions favorable for wind and water erosion.However, it is possible to perform qualitative analyses of the environmental impacts of aggregate, stone, and industrial mineral mining for relatively small areas.

The most recognized health hazards from these mines involve airborne particulate emissions. Total Suspended Particulates is a measure of all particulates emitted by a mine, while PM-10 particles represent some of the smallest particles (<10 _ in diameter) that can stay suspended in the air for long periods and pose the greatest respiratory health hazards. Some industrial minerals, like perlite and silica flux, create extremely fine particles of silica that can cause silicosis on prolonged exposure. Gypsum mines can also produce very fine gypsum ([Ca(SO)4. 2H2O] dust that can irritate the lungs and mucus membranes. All other types of aggregate and sand mining involve the excavation, crushing, and screening of rocks that are predominantly Al-Mg-Fe-silicates, except for limestone and caliche, which are calcium carbonate. None of the minerals contained in these types of rocks is known to cause heavy- metals poisoning or cancer, and the potential health risks posed by TSPs from these minerals involve respiratory problems caused by chronic irritation of the lungs and mucus membranes.Many air quality permits require that sampling be done only once every 7 days for one 24-hour period, which means that the air quality at a given mine or mill is sampled only 14% of the time. Thus, the mine is allowed to choose when these samples will be collected, which means that sampling can be avoided on extremely windy days and can usually be done under calm conditions. This selective sampling allows the permittee (the mine and/or mill) to remain in compliance with the air quality permit even though its operation may be violating terms of the permit the majority of the time. Although the mine must meet TSP standards for 24-hour, 7-day, and 30-day averages, these measurements are taken from a stack and do not include TSPs from pits, haul roads, and disturbed areas on the property.

One environmental impact that is often a problem in more temperate climates is the sediment load produced to surface water by aggregate, stone, and industrial mineral mines. In wetter areas of the United States, the sediment loading from these mines to streams, bays, lakes, and wetlands has been identified as a source of significant degradation to water supplies. Mines are required to capture surface water runoff and treat it on site, generally in settling ponds where the sediments drop out of the ponded water. However, because of the semi-arid climate in New Mexico, where annual precipitation in lower (<6000 feet msl) elevations ranges from 4 to 12 inches, very few perennial streams exist. Consequently, excess sedimentation in surface runoff from mines is generally not a problem except in those instances where a sand and gravel (or industrial mineral) mine is located immediately adjacent to a perennial stream. All permitted mines must comply with NMED ground and surface water quality standards. Most mines comply with water quality standards by installing silt fences or sediment basins to capture sediments on the permitted property.Generally, aggregate and stone mines do not produce materials containing heavy metals or radionuclides. Because no current or historical aggregate or stone mines are known to have produced ARD (Acid Rock Drainage), acidic runoff containing heavy metals is not considered to be an environmental problem at these mines. However, aggregate and stone mines are not required by either NMED or MMD to conduct analyses for heavy metals or radionuclides in their permit applications, so no such data have been collected for these mines. Because some areas of the Rio Grande Valley contain small deposits of uranium (e.g., several small abandoned uranium mines/prospects on Cochiti Pueblo east of the Rio Grande), it would be appropriate to test for radionuclides if there is evidence of uranium mineralization in the deposit to be developed.

Another major environmental impact from aggregate and stone mines is groundwater use. Because mines are required to wash some materials on site and also control dust, some mines use millions of gallons of scarce groundwater to perform these tasks. Although dust control is necessary at these mines, the use of scarce potable water for dust suppression must be weighed against the increasing demands of domestic water use. Some operations, like the Oglebay Norton mica mill in Velarde, have secured water rights for hundreds of acre-feet of water use per year. This mill also receives an 80% "return flow credit" for water discharged to tailing ponds that is alleged to infiltrate into the alluvium and "return" to the Rio Grande alluvial aquifer. It is extremely unlikely that anywhere close to 80% of the water used by this mill "returns" to the aquifer. Although the New Mexico State Engineer's Office is supposed to regulate all groundwater development, most aggregate and stone mines (as well as many industrial mineral mines) develop and use water wells with little or no oversight from the state. Consequently, the actual amount of water used by such mines and mills is unknown.

3.1 Cumulative and Associated Environmental Impacts

The most obvious environmental impact from aggregate, stone, and industrial mineral mines is degraded air quality, and associated health effects, resulting from airborne emissions from both the stack and the disturbed areas at these mines. In an arid landscape like New Mexico, the impacts of such mines on surface and groundwater quality is not likely to be significant. However, these mines should be viewed as a first step in development, whether it is highway, residential, or general construction. When one tracks a truck load of sand and gravel from its excavation, through loading and hauling, and to its ultimate use as either fill dirt, base course, cement, or some other construction use, it becomes clear that the environmental impacts of sand and gravel mining are widespread and cumulative. Below is a partial list of the potential cumulative impacts from the development of a typical sand and gravel mine.

--Dust and diesel fumes generated on the haul road to and from the mine.

--Fugitive dust blowing from the uncovered or partially covered dump trucks.

--Fugitive dust from poorly monitored crushers and out-of-compliance operations.

--Fugitive dust from piles of sand and gravel at the construction sites.

--Fugitive dust from the spreading of sand and gravel at the construction site, whether highway or building construction.

--Increased traffic (highways) or population (building construction), with a concomitant increase in air pollution from more vehicles (highways and rural roads) and more disturbed land (building construction).

--Increased air pollution from some sand and gravel mines after they are abandoned and until natural re-vegetation stabilizes the surface soil.Each of the impacts listed above produces real-world effects that are difficult to measure. In the past, smaller populations and lower levels of development made these impacts less noticeable. But with larger populations and development that consistently outstrips the government's ability to regulate its impacts, the cumulative effects of aggregate and stone mining, especially in urban areas, contribute to the overall degradation of the environment. In rural areas these impacts are also serious for affected local communities.

A related impact from aggregate and stone mining is increased traffic congestion and safety hazards in both small rural communities and urban areas. Unlike metals or coal mines where most of the truck traffic occurs on private mine property, aggregate, stone, and industrial mineral mines create traffic on public highways. For example, the Oglebay Norton mica mine near Peñasco hauls ore 35 miles one-way along narrow, two-lane mountain roads to a mill in Velarde, which is located in a very congested area in the Rio Grande Valley. Another example is a currently inactive crushed rock mine north of the village of Los Cerrillos. When this mine was operating, trucks drove through the village 8 hours per day and created dust, noise, diesel fumes, and general congestion in this small historic community. Wherever such mines are located, it is common to note traffic hazards as trucks enter and leave public highways dozens of times each day.

Another important impact of aggregate and stone mining is aesthetic degradation. The major transportation corridors of New Mexico (I-40 East-West; I-25 North-South) were built with local materials, as are all highways. Drivers on I-40 and I-25 crossing New Mexico can see hundreds of abandoned pits and dozens of active aggregate and stone mines from the highway. Sprawling urban areas like Albuquerque and Santa Fe-Española are pock-marked with huge sand and gravel pits. Although these mines made highway construction less expensive, their impacts on the scenic viewsheds across New Mexico are significant.

One final impact created by these mines could be called the "public nuisance" effect. For years certain operations, like the Dicaperl perlite mine and mill in Socorro or Oglebay Norton mica mill in Velarde, have been emitting dust that disturbs neighbors. The state has not been effective in making either of these operations control their emissions and nearby homes are often covered with a fine layer of perlite or mica dust from the mill. The Velarde mill also frequently operates at night and makes enough noise to disturb neighbors as far as a mile away. The combination of bright lights to aid night operations, loud noises from crushers and screen plants, and chronic dust emissions creates a public nuisance for those people unfortunate enough to live near such operations.

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

Aggregate, stone, and industrial mineral mines are common across New Mexico. Although aggregate and stone mines are not regulated under the New Mexico Mining Act, they are registered with MMD and permitted by NMED for air and water quality purposes. The primary environmental impact from aggregate, stone, and industrial mineral mines in New Mexico is degraded air quality from stack emissions and disturbed areas on the mine. Surface and groundwater quality impacts from such mine are relatively benign in New Mexico due to the semi-arid climate and lack of perennial streams. Other environmental impacts include increased traffic on new or improved roads; cumulative impacts as construction materials are hauled, stockpiled, and spread on highway and building construction projects; and aesthetic degradation caused by aggregate, stone, and industrial mineral mines in major viewsheds.

Existing environmental laws are limited in scope in regulating aggregate and stone mines in New Mexico. All but the largest of these mines are considered minor sources of air pollutants and are allowed to emit limited quantities of Total Suspended Particulates, sulfur compounds, nitrogen dioxide, and Volatile Organic Compounds. These emissions may be considered nuisances in certain rural communities (e.g., Velarde, Los Cerrillos, Socorro), but the state does not consider these impacts to be significant or to pose serious public health hazards. Existing regulations do not account for the concentration of such mines in and around urban areas where the majority of highway and building construction occurs. Because aggregate and stone mines are exempted from reclamation and regulatory requirements under the New Mexico Mining Act, these mines are not required to re-vegetate or reclaim their operations. Consequently, hundreds of abandoned and inactive mines are located in every county of the state.

Mitigating the environmental impacts of aggregate, stone, and industrial mineral mines could be improved by making some changes to existing regulations and, most importantly, by controlling development and sprawl in both urban and rural areas of the state. The following recommendations are made to better manage environmental problems and mitigate the effects of aggregate, stone, and industrial mineral mines.

1. Deny operating permits to new operations if inactive or abandoned mines could be re-opened to provide the same resource. New operations should be permitted only if no other suitable materials are available in a given area. This would make better use of existing resources in areas where disturbance has already occurred and prevent the random and incoherent development of aggregate and stone mines.

2. Enforce existing mine and mill air quality permits strongly and consistently. The state seldom enforces the terms of air quality permits and rarely issues Notices of Violation or fines allowed under the Air Quality Act. This would require that the state hire more inspectors and make certain "problem" mines and mills come into compliance to set an example for all operations.

3. Deny permits to mines that propose locating in areas unsuited for mining. Mines should not be allowed to operate near Native American "sacred sites," residential neighborhoods, historic rural communities, or in areas where the resulting "scar" will ruin a scenic viewshed.

4. Encourage the use of re-cycled materials like "glassphalt," "plasphalt," and used tires to replace aggregate, crushed rock, base course, sand, and gravel in highway construction. This would reduce the need to open new mines and help with the problem of overloaded landfills. Because re-cycled materials are not currently competitive with many highway construction materials, the state and federal government will likely have to subsidize the use of re-cycled materials. However, over time it is likely that re-cycled materials will become more widely used and the cost differential between road construction materials and re-cycled materials will narrow.3. References

Hawley, J.W., 1978, Guidebook to the Rio Grande rift in New Mexico and Colorado: Circular 163, New Mexico Bureau of Mines & Mineral Resources, Socorro, 241 pp.

New Mexico Mining and Minerals Division, New Mexico Bureau of Mines & Geology, New Mexico Bureau of Mine Inspection, 2001, Mines, Mills, and Quarries in New Mexico; 46 pp.

New Mexico Environment Department Web page (www.nmenv.state.nm.us), 2003, Air Quality Bureau Web page (includes Permitting Section, Ambient Air Quality Standards, and Dispersion Modeling Section), New Mexico County Land Use Regulations.

~ Rural Conservation Alliance

PO Box 245

Cerrillos, NM 87010

murlock@raintreecounty.com

Page managed by RIII http://www.raintreecounty.com/Blodgett.html